The Politics of Disorder

From Nixon to Ancient Rome, fear of disorder has always had a vital role in politics

Disorder has been at the heart of President Trump’s chaotic political career ever since he first announced his electoral ambitions, and for good reason. Trump has repeatedly positioned himself as the candidate that can restore order to a fractured, broken and disordered nation, tying together fears of crime, lawlessness and societal chaos as a central part of his message.

The most memorable part of Trump’s 2017 inauguration speech was his vow that “This American carnage stops right here and stops right now” – a line which reverberated around the coverage of the day in both national and international media. With growing polarisation over campus protests across the US, Trump has quickly seized upon the opportunity to present himself as the sole candidate that can restore order.

The concept of law and order is nothing new to democratic politics, and its influence expands much further than Donald Trump. In the UK, both the Conservative and Labour parties have attacked each other over their record on law and order, with it likely that both major parties will pledge to toughen sentences for criminals and fund more policing as part of their election manifestos. Likewise, across Europe, North and South America, Africa and beyond, fears of lawlessness have consistently polled as a top concern among electorates – alongside major challenges such as the economy, healthcare and national security.

History teaches us that law and order can play a crucial role in democratic politics, providing ammunition in fiercely fought election campaigns and a rallying cry for political support. By examining two different political events – Richard Nixon’s 1968 campaign for the White House, and Pompey the Great’s push to restore order to the late Roman Republic – we can get a glimpse into how disorder can decide key political moments.

Nixon, disorder and Vietnam

On the day of the 1968 Presidential Election, both the Republican nominee, Richard Nixon, and the Democratic candidate, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, could sense that the winning margin would be tight. Both Nixon and Humphrey had fought a tumultuous campaign in which public disobedience – both civil and uncivil – had become commonplace across parts of the United States. In 1968, the US found itself in a pre-revolutionary atmosphere, with race riots and anti-war protests dominating the headlines.

Urban race riots had become a common occurrence in major cities since the mid-1960s, spurred by clashes over civil rights and racial discrimination. Following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr in April 1968, race riots broke out on a fierce scale in cities such as Washington D.C., Chicago, Baltimore and Kansas City, in which looting, arson and clashes with police were commonplace. In the 10 days following King’s assassination, over 200 cities saw rioting, with 43 people killed, over 27,000 arrested and millions of dollars’ worth of property destroyed.

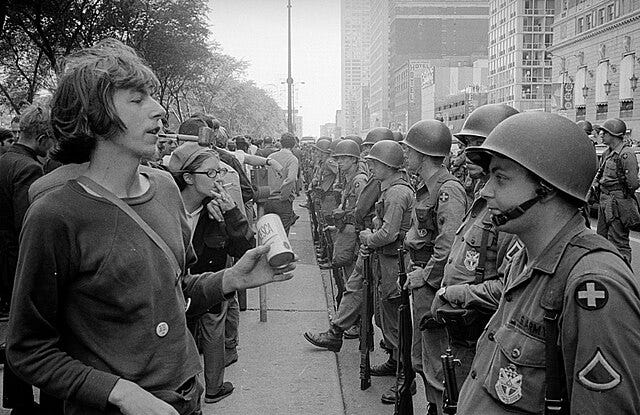

Race riots were not the only source of disorder during the 1968 campaign. The Vietnam War, as both the scale of the war and American casualties grew, had seen strong opposition from student groups and become another central issue of the campaign – with students regularly taking over university buildings in protest against the war. The culmination of this anti-war fervour was the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, in which Humphrey was formerly named as the Democratic nominee. 10,000 anti-war protesters descended on the convention, which in turn was met with force by 23,000 police officers and members of the National Guards. Disorder broke out both inside and outside the convention, with the event overshadowed by chaos.

To a crafty politician like Nixon, this was the political opportunity of a lifetime. Nixon’s message to the American public was simple – he positioned the election as a choice between disorder, rioting and chaos with the Democrats, or law and stability under a Nixon presidency. Nixon declared that growing violence “is the work of other Americans, transformed into a mob” and that “the spirit of vandalism” had become commonplace on university campuses.

Nixon pledged to bring an end to the disorder and contrasted his strong law and order message against that of the Democrats, presenting the silent majority as being “sick of what has been allowed to go on in this nation for too long.”

Time and again, the theme of law and order permeated throughout the 1968 campaign, with further events – such as the assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy, and the candidacy of independent George Wallace, a brash populist and fierce opponent of desegregation – further underscoring the deep fault lines that ran through the nation. But in the end, Nixon’s pledge to end the disorder won the day – and he was elected president by 301 electoral votes to Humphrey’s 191. Law and order proved to be a vote winner.

Pompey, Cicero and disorder in Rome

Nixon’s 1968 victory may have been a turning point in US politics, but the history of the late Roman Republic highlights that law and order politics have deep roots. In 52 BC, Roman society was also beset by street violence and a deep sense of disorder. The chaotic events of 52 were tied to the rise of Publius Clodius Pulcher, a populist politician with a chequered past marked by scandal. A few years prior, in 58, Clodius was elected as tribune and used the position to attack members of Rome’s political establishment - targeting Marcus Tullius Cicero, Rome’s greatest orator and a former consul.

Clodius used Cicero’s time as consul (the top political position in Rome) as ammunition against him. Previously, in December 63, Cicero had stopped a plot to overthrow the government and assassinate the senate by a disgruntled politician called Catiline, and promptly put Catiline’s supporters to death for their role in the plot.

The moment marked the crowning glory of Cicero’s consulship, but five years later it would come back to haunt him. Clodius enacted laws to prevent the execution of Roman citizens without a trial and brought charges against Cicero, retrospectively, for his actions as consul. Cicero argued that the law was ad hominem and targeted personally towards him, which was illegal under Roman law. But Clodius gathered his rowdy supporters onto the streets and ordered them to intimidate anyone that sided with Cicero – forcing the former consul into exile.

Clodius had won an enormous victory against Cicero and the establishment. After triumphantly having Cicero’s house on the Palatine Hill destroyed and a temple dedicated to Liberty erected in its place, he would then forge an alliance with Gaius Julius Caesar and continue his campaign against the Optimates – the conservative faction in the senate, led by politicians such as Marcus Porcius Cato. But the mob tactics used by Clodius made him deeply unpopular with the establishment, who opted to use his own strategy against him.

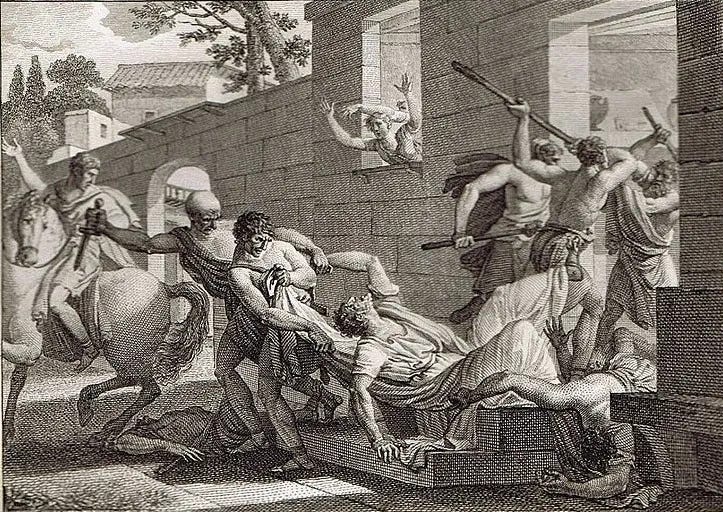

The fightback against Clodius and his mob was led by Pompey the Great, a former consul and distinguished general who pushed for an end to the violence and Cicero’s return to Rome. Clodius and his mob once again took to the streets and violence ensued, with Cicero’s own brother, Quintus, almost losing his life. It was at this point that Pompey realised he had to use the forces of Clodius against him, promising to restore law and order to the streets of Rome by brute strength.

The conservatives found their own firebrand, Titus Annius Milo, who was able to call his mob onto the streets and push the supporters of Clodius out of the forum. Cicero’s recall was then put to a vote, with the historian Plutarch remarking: “it is said that the people never passed any vote with such unanimity.” Pompey and Milo had managed to restore order and save Cicero, but further violence was yet to come.

The next flareup would arise in 53, when Milo announced his candidacy for the consulship. Street battles between the gangs of Clodius and Milo were a running theme of the campaign, with the situation becoming so volatile that the elections had to be postponed. On 18 January 52, Clodius and Milo would encounter each other by chance outside of the city – and fighting once again broke out. This time, Clodius was fatally injured in the violence and his supporters back in Rome marched into the forum. The Greek historian Appian recounts the disorder that followed:

“There the most reckless ones collected the benches and chairs of the senators and made a funeral pyre for him, which they lighted and from which the senate-house and many buildings in the neighbourhood caught fire and were consumed along with the corpse of Clodius.”

With the violence reaching a tipping point, Pompey once again saw an opportunity to become the voice of law and order. The senate passed a Senatus Consultum Ultimum – a declaration of emergency – which enabled Pompey to raise troops and restore order in the city.

The senate then cancelled the elections for the year and took the unprecedented move of granting Pompey a sole consulship, allowing him to use his troops to oversee the prosecution of Milo and bring an end to mob rule in Rome. Order was restored – and Pompey had gained a political victory by positioning himself as the politician of law and order.

These two examples, from Washington D.C. to Ancient Rome, are both set against the backdrop of highly different social, political and cultural environments, with over 2000 years separating Nixon from Pompey the Great. But the lesson of both is the role that disorder can play in democratic politics, and the way in which crafty politicians can use popular fear of disorder to their political advantage.

From the forum to the White House, it is certain that the 2024 US election will see a similar move by Donald Trump to present himself as the ‘defender of order’. Only time will tell whether this move will pay off politically, but history informs us that it may well prove fruitful.