The Long Telegram

Kennan, the Soviet Union and US foreign policy

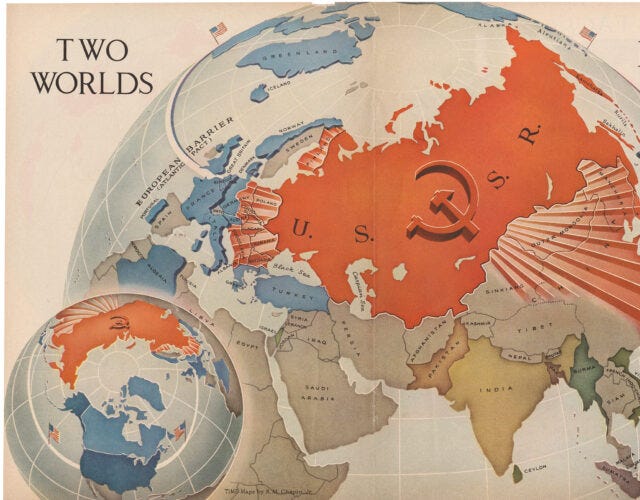

In 1946, leaders in the United States, Europe and the Soviet Union understood that the world was at a crossroad. At the end of World War Two, the relationship between the two great world powers – the US and the Soviet Union – would come to dominate the geopolitical scene, leaving onlookers to closely watch any signals from Moscow and Washington to try and understand their intentions.

Analysing the ideology, fears and ambitions of the American capitalists and Soviet communists became crucial to understanding world affairs, with both sides of the Atlantic still coming to terms with the nature of the civilizational clash known as the Cold War that was to follow.

For the historian, the reliance on primary sources and original evidence can be both our greatest tool and our most significant source of frustration. Backroom deals, informal discussions and destroyed documents can leave historians with an incomplete picture, with our understanding of world history often left to conjecture or guesswork.

It is fortunate that when it comes to the Cold War, and specifically the founding principles of US-Soviet relations, the Long Telegram provides a window for historians to understand this crucial period of world history. The Long Telegram was a response given by George F. Kennan, Deputy Chief of Mission at the United States Embassy in Moscow, in February 1946 to a Treasury Department request for an assessment on Soviet policy – specifically around the Soviet decision to decline participation in the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank.

The response that they and the wider US diplomatic community received was not quite what they had expected. Kennan’s telegram was a masterpiece of political analysis: over 5000 words long, it contained a thorough assessment of Soviet politics, drawing on a range of themes from Marxist ideology to Russian history, alongside his views on how the US should approach the Soviet Union in the post-war era.

The Long Telegram was later expanded on and published in Foreign Affairs magazine in July 1947 under the title “The Sources of Soviet Conduct”, with Kennan writing anonymously as ‘X’ under instruction from the State Department. Known as the X Article, Kennan would proceed to develop his argument and lay the intellectual foundations for the US policy of containment towards the Soviet Union. So, what argument did Kennan present, and what was its long-term impact?

Kennan and US-Soviet Relations

Central to the view Kennan developed in both the Long Telegram and the X Article was his deep understanding of Russian history – and Bolshevism in particular. The early years of the Soviet Union, beset by a bloody civil war and foreign intervention by Western powers, made the communist leadership view dictatorial power as a complete necessity.

The transition of power to Stalin after Lenin’s death had ended the chance of any reduction of this dictatorial power, and the nature of the Communist Party meant the co-existence on a permanent basis of rival sources of power was unacceptable to the Kremlin.

Kennan emphasized that the Kremlin leadership was primarily motivated by their own security: both in terms of internal threats and plots, and pressure from the outside world. This was both the nature of Soviet ideological doctrine and a result of Russian history.

This instinct became increasingly influential in Soviet foreign policy as the internal role of capitalism was swept away in the years after the Russian Civil War, with the absence of a capitalist threat at home making the existence of a capitalist threat from abroad even more necessary.

To the Soviet eye, capitalism contains the seeds of its own destruction, and imperialism (as the highest form of capitalism) can only lead to war and revolution. Hence, the outside world was inherently aggressive and hostile, but doomed to failure, with the Soviet Union tasked with ensuring the survival of the party until the inevitable proletarian revolution took hold in the capitalist world. As Stalin said himself in 1924: “as long as there is a capitalist encirclement there will be danger of intervention with all the consequences that flow from that danger.”

In essence, Soviet policy towards the outside world was therefore driven by the necessity of explaining, maintaining and defending its dictatorial policy at home. Soviet actions domestically (such as political repression, secret police and gulags) may make foreign powers more hostile to the state, but the notion of a hostile world must be maintained to justify that oppression.

The need of the party to remain the sole source of legitimate authority in Soviet society also meant that the state must be infallible. Therefore, truth becomes not an immutable, objective reality, but the day-to-day view espoused by Stalin and the Communist Party. In Kennan’s words, truth was whatever serves the Kremlin leadership “because they represent the logic of history.”

In both the Long Telegram and X Article, Kennan posited that this was not solely a product of Marxist philosophy, but also a result of Russian history. An agricultural society surrounded by nomadic marauders to the east and more developed states to the west, Russian leaders had historically seen themselves as constantly threatened by the outside world.

Conscious of their archaic and primitive political system, Russian rulers felt threatened by their internal weaknesses, and saw foreign influence – both directly in a politico-military sense and indirectly through outside ideas and concepts – as a challenge to their authority and position.

The influence of climate, agricultural development and political traditions from the Asiatic world all left Russian rulers feeling challenged by the outside world – and this heavily influenced Russian foreign policy throughout the centuries. Hence, Kennan identified that Russian rulers were naturally hostile to the outside world, viewing contact between European powers and their own people as a destabilizing influence, which risked the collapse of their regime.

Soviet conduct

In Kennan’s eyes, the necessity of presenting an external enemy to their own people explained many of the characteristics of Soviet foreign policy: secretiveness, extreme suspiciousness, a tendency for duplicity and a generally hostile approach to international relations. In the X Article, he noted:

“If the Soviet Government occasionally sets its signature to documents which would indicate the contrary, this is to be regarded as a tactical manœuvre permissible in dealing with the enemy (who is without honor) and should be taken in the spirit of caveat emptor. Basically, the antagonism remains.”

Kennan stressed that this did not mean that the Soviet threat was imminent, but that it was permanent. Given the socialist understanding of the ‘inherent contradictions’ of capitalism, its fall did not have to be immediate, and indeed, foreign adventures and revolutionary activity that in turn brought pressure on the Soviet Government would be actively avoided by the regime.

To Kennan, the internal system of Soviet politics and its ideological commitment to the overthrow of capitalism was both a spotlight and a cloud over Soviet foreign policy. He viewed the Soviets as being more willing to back down and compromise when facing superior force, safe in the knowledge that the defeat of capitalism was inevitable and therefore non-urgent in the short term.

Kennan warned that, on the other hand, this ideological strand left the prospect of a single, conclusive victory through one battle or confrontation as impossible, with the Soviets not discouraged by even severe setbacks. This meant the US and its allies would need a strategy of long term, patient and firm commitment to halting Soviet power – or in other words, containment.

In essence, Kennan concluded that a tough but measured approach to the Soviet Union, in which the US would “remain at all times cool and collected and that its demands on Russian policy should be put forward in such a manner as to leave the way open for a compliance not too detrimental to Russian prestige.”

He noted that the Soviet political system, with its ridged political hierarchy, total need for obedience and disconnect between rulers and subjects could in turn leave the Soviet Union vulnerable in the long term, with its ability to transfer power effectively between leaders still an unproven element of Soviet politics in the late 1940s. In his closing remarks, Kennan summarized the coming contest of the Cold War as follows:

“The issue of Soviet-American relations is in essence a test of the over-all worth of the United States as a nation among nations. To avoid destruction the United States need only measure up to its own best traditions and prove itself worthy of preservation as a great nation.”

The lessons of containment

Kennan’s views would lay the framework for US policy towards the Soviet Union in the years to come. In 1947, the Truman Doctrine declared American intentions to provide economic and military support to nations threatened by communism. One year later, the Marshall Plan would provide economic aid to countries devastated by the Second World War, with its humanitarian ambitions serving a key political objective – to prevent the spread of communism in Europe.

In 1949, NATO was established as a military alliance of Western nations with the objective of utilizing collective defence to protect against Soviet expansion. In other words, these measures would use economic and military levers to contain Soviet influence and prevent the spread of communism without provoking a direct military confrontation.

Kennan would eventually become a critic of how various US administrations implemented his policy of containment. He stressed that the changing emphasis from his own focus on diplomatic, economic and political pressure to a growing military arms race risked a direct confrontation with the Soviet Union – which ran counter to his original vision.

Kennan would continue to champion a more nuanced version of containment throughout the Cold War, in which the limitation of communist influence via non-military means would eventually bring about an American victory.

In essence, through the Long Telegram and X Article, Kennan concluded that just as the Soviet leadership believed capitalism produced the seeds of its own destruction, Soviet totalitarianism could also do the same. He portrayed the looming Cold War as a clash of civilizations, with Soviet policy being deeply rooted in both the early years of the young Soviet state and the wider experience of Russian history.

While others urged the US to come to terms with the Soviet regime, or pushed for a policy of direct confrontation with Moscow, Kennan used his deep understanding of Soviet politics to sketch a very different geopolitical strategy. The Long Telegram provides us not only with a direct insight into Kennan’s policy of containment, but also the wider ideological clash between the two camps of the Cold War.

If today’s politicians are to take a lesson from the Long Telegram, it is that to defeat your enemy, you must first understand their history, politics and internal system. Kennan understood this – and the Western world today is undoubtedly better off because he did so.