History, Power and Paranoia

What the reimagining of Bratislava Castle can teach us about totalitarianism

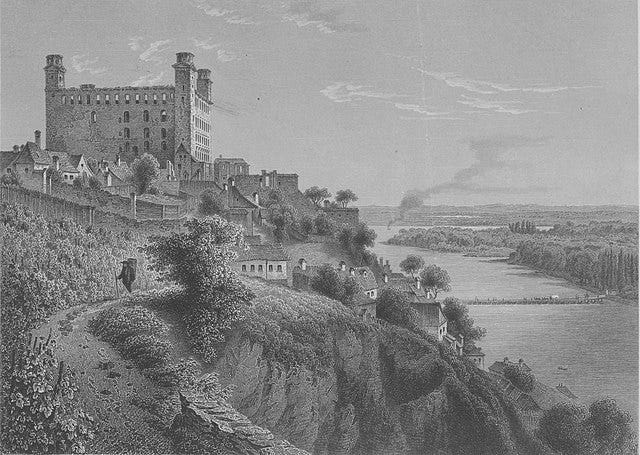

On arriving in Bratislava, the capital city of Slovakia, it is practically impossible to miss the imposing figure of Bratislava Castle. Towering high above the urban metropolis below, the baroque castle serves as a potent symbol of both the city and the Slovak nation, featuring on everything from the Slovakian Euro notes to an endless stream of branding and marketing materials.

This is for a good reason. The castle, rectangular shaped with four corner towers and glistening in dazzling white paint, impresses with its beauty – and provides an enduring reminder of the city’s history. From the Romans to the Moravians, to its time as a fortification of the Hungarian kingdom and later an outpost of the grand Austro-Hungarian Empire, Bratislava Castle prompts us to consider the great empires that have controlled the city over the years.

However, its more recent history also provides a crucial insight into the modern history of Slovakia, alongside offering an important lesson about the nature of totalitarian regimes.

Rise and fall

The castle itself has a tumultuous history. Ruins within the castle grounds date back to the Roman Empire, when the Danube River became the natural border of the empire in the first century BC. The fortress that sat upon on the site would later feature in the first written record of Bratislava, the Annals of Salzburg (907 AD) in connection with a battle fought between the Hungarians and Bavarians in the region.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the fortress would be rebuilt, expanded and fortified, with a gothic castle eventually being constructed during the reign of Sigismund of Luxembourg. However, it would be in the Early Modern period that the castle began to take the form that we see today. An expanded gothic castle was constructed in the 16th century, and in the 17th century it was rebuilt in a baroque style.

During the reign of Maria Theresa (Habsburg ruler between 1740-1780), the castle was again refashioned to suit the needs of her son-in-law, Albert of Saxony-Teschen, who, as royal governor of Hungary, used Bratislava Castle as his residence. A passionate art collector, Albert used the castle as a cultural sphere and to showcase his own collection. It was during this time that many of the castle’s iconic features, such as the white and gold grand staircase, were built – bringing a sense of Habsburg grandeur to what had once been a practical fortification on the Danube.

The rise of Bratislava Castle showcases the fortunes of the authorities who fought to control the region, but the castle’s fall was equally dramatic. As Bratislava’s importance in the Habsburg Empire lessened, the castle reverted to being a military barracks – with this decision having enormous consequences. On 28 May 1811, the castle was ravaged by a fire and engulfed in flames. Caused by the carelessness of a solider, the fire burned for three days and completed gutted the castle.

The ruins of Bratislava Castle would sit like a rotting corpse above the city, left untouched for nearly 150 years. In the 20th century, plans were proposed to rebuild the castle or even demolish it completely and replace it with modern administrative buildings, but disagreements over the plans left the castle frozen in time, a shadow of its former self. But once communism arrived in the country, this would soon change.

Totalitarianism and restoration

At the end of the Second World War, Slovakia, which had been a one-party state governed by allies of Nazi Germany, was liberated by the Red Army in 1944-1945 – and found itself behind the Iron Curtain and now under the sway of the Soviet Union. The ruling communist party of the re-established Czechoslovakian state set to work rebuilding the country under their own doctrine, and the fate of Bratislava Castle once again resurfaced.

In 1953, the authorities allowed archaeological research to begin within the castle grounds, with the reconstruction of the castle then beginning in earnest. A number of notable figures were involved in the reconstruction, including the renowned Slovak painter Janko Alexy and architect Dušan Martinček, who worked on the castle between 1958 and 1976.

However, the most interesting – and tragic – figure involved in the restoration was Alfréd Piffl, a Czech architect and passionate preservationist. Piffl’s background was nothing short of impressive: after graduating from Czech Technical University in Prague and spending his early career designing posters in an advertising department, he soon found a new calling in preservation architecture, taking up a position in the State Archaeological Institute in Prague.

After a spell working on some of the most significant archaeological sites in Czechoslovakia, Piffl defended his doctoral thesis in 1937, before progressing after the Second World War to prestigious lecturing roles at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague and his alma mater, Czech Technical University. During this time, he would organise a number of major exhibitions and protected important artwork from thieves in the immediate chaos of the post-war world.

In 1946, Piffl’s career reached new highs, as he became professor of the history of architecture at Slovak Technical University, where he would lead a newly founded institution, the Faculty of Architecture and Civil Engineering. It was this position that would take Piffl to Bratislava, setting the stage for a tumultuous contest between Piffl and the authorities over the castle.

Between 1953 and 1957, Piffl devoted his life to faithfully restoring Bratislava Castle, where he painstakingly oversaw the reconstruction to ensure the historical features of the castle were accurately preserved. The task was gargantuan, as Piffl laid out in his diary: “It will take tremendous effort because we're starting from scratch”. His enthusiasm for the work was unmatched, with the professor proclaiming in one diary entry from 21 April 1954:

“So the work began! It is a huge nervous commitment, work for years. I don't know if I will be enough for it, but I feel a kind of ripple, the presence of unknown forces is driving me to work, and I believe that I will be able to finish it.”

However, the work took a heavy toll on Piffl. In another diary entry, he exclaimed:

“How many hours have I devoted to the castle! Like, merely studying the mortars, plasters and stones. All those Sundays that I devoted to the castle in discomfort and at the expense of my family. Hours and hours of study! But a communist primitive cannot see that!”

Despite his painstaking efforts, Piffl’s dream of restoring the castle would come crashing down as he fell foul of the authorities, who in 1957 imprisoned him for two years on charges of ‘public sedition and slandering a friendly power’. The true cause of his arrest is still unknown – rumours of a tunnel in the castle well through to neighbouring Austria was one such story, or another (perhaps more plausible) version of events suggests that Piffl had offended a local functionary who was visiting the castle well.

For Piffl, this marked the end of his work on Bratislava Castle. He was stripped of all his academic titles by the authorities, and after leaving prison in 1959 worked several menial jobs to make ends meet - including at a panel factory in Trnávka and later at a building office.

Towards the end of his career, Piffl was able to return to archaeology, working on various important sites around Czechoslovakia (including the famous Devín Castle, outside of Bratislava). However, he would never again return to Bratislava Castle, with other architects like Martinček taking over his work and completing the restoration in the late 1960s. The castle now stands pride of place on the hilltop above Bratislava Old Town. On 25 June 1972 Piffl suffered a stroke, passing away the next day.

The dual fate of Bratislava Castle and Alfréd Piffl tells us a great deal about the regimes that controlled the nations behind the iron curtain, alongside the relationship between history and totalitarianism. For the castle, it is no coincidence that the communist regime opted to push ahead with the restoration – with its reconstruction blending the communist exploitation of the past with political objectives. To quote art historian Ján Bakoš in his study of the castle:

“As we know, communism systematically exploited the past and its remnants for its own purposes. Moreover, official art in the communist era, "socialist realism", was a specific kind of historical revival and as such mixed the past with the present to construe an ideal pretended reality. The attempt to mask the expansive, world-domineering nature of communist ideology and legitimise its hegemony forced the totalitarian regime to allow a certain degree of nationalism into the official ideology.”

If the reconstruction of the castle showcases the ‘world-domineering nature of communist ideology’, Piffl’s own fate shows the disdain of the regime towards individual liberty. A state driven by a fierce ideology left individuals - even those of great talent such as Piffl - at the whims of party functionaries, jealous officials and overzealous bureaucrats.

Without a fair trial and protection from the state, those seen as ideological enemies could be purged at will in the name of doctrine. The magnificent spectacle of Bratislava Castle today reminds us of the ways in which history can be transformed and refashioned – and the high price that some individuals would pay in defence of the traditional.