Banishing the Philosophers

Cato the Elder and Roman conservatism

Societies have always faced challenges to their traditional values, especially when the values of their elites have diverged from the rest of the citizenry. Ancient Rome experienced this same tension between new values and ideologies from the East and what many traditionalists viewed as Rome’s moral virtues.

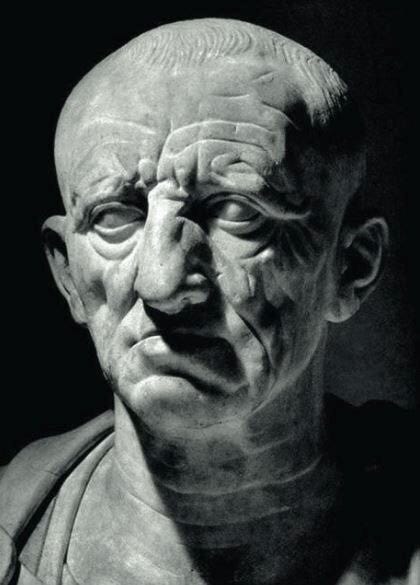

The face of this contest between the new and the old in the first century BC was Marcus Porcius Cato – also known as Cato the Elder (234-149 BC). Cato built has career through military successes, rising to the top of Roman politics from humble origins. But he is best known for his fierce opposition to the Hellenization of the Roman aristocracy and the departure of the elite away from traditional Roman values. Cato’s career and the battle of ideas he engaged in with this elite provide an insight into the changing nature of elite ideology, both in the ancient world and today.

Cato wasn’t born into the Roman elite. He was born in Tusculum, a provincial city outside of Rome, to a family who were part of the local aristocracy but certainly not a Roman patrician family. Cato’s world was shaped by the Second Punic War, which began in 218 BC and saw Hannibal crossing the Alps and invading Italy. Cato enlisted in the army at seventeen and spent the next thirteen years campaigning across Italy, where he rose through the ranks and became a military tribune.

After the war ended with a Roman victory in 201 BC, Cato was able to leverage his military exploits to build himself a political career. He served as quaestor (204 BC), aedile (199 BC) and praetor (198 BC), where he built a reputation for moral discipline and the rejection of luxury. As praetor, he was tasked with governing the Roman province of Sardinia, where he undertook an anti-corruption campaign and massively reduced his expenses as governor.

During this time, he gained the support of a powerful member of the Roman aristocracy, Lucius Valerius Flaccus, who helped to legitimise Cato in the eyes of the Roman elite. Through his relationship with Flaccus, Cato would reach the pinnacle of Roman politics and was elected consul in 195 BC. Cato’s commitment to traditional Roman ideals and the ‘simple life’ had gained him many admirers both in Rome and abroad, with Plutarch noting that he “was contented with a cold breakfast, a frugal dinner, simple raiment, and a humble dwelling, — one who thought more of not wanting the superfluities of life than of possessing them, — such a man was rare.”

As consul, Cato would clash a number of times with others on ideological grounds. He opposed the repealing of the Lex Oppia, a law devised during the Punic War to limit the amount of wealth that a woman could hold. Specifically, the law forbade women to possess more than a certain amount of gold and outlawed the wearing of multicoloured garments, all in the name of driving down spending on luxury items during the difficult war years.

With the war now over, attempts were made to have the law repealed – but Cato opposed this vigorously, claiming that once this limit was removed, women’s spending would become uncontrollable, and luxuries would further permeate across Roman society.

Crowds of women gathered around the Forum and asked senators and officials to repeal the law, with Flaccus himself supporting their cause as the other consul for the year. Their opposition was too strong, and Cato’s attempt to preserve the law eventually failed, and it was repealed that year. The affair highlights Cato’s fierce attempts to resist any change that he felt eroded Roman values and its traditional culture.

After his year in office as consul, Cato was granted a command in Spain, where his successes generated vast riches from the mines in the region. He was generous with this loot, with Plutarch proclaiming that Cato felt “it was better to have many Romans go home with silver in their pockets than a few with gold.”

However, Cato himself did not partake in this loot, stating “I prefer to strive in bravery with the bravest, rather than in wealth with the richest, and in greed for money with the greediest.” Further campaigning in Greece would follow, with Cato heavily involved in Rome’s war and eventual victory against Antiochus III.

Banishing the philosophers

By this time, Cato was both a distinguished commander and politician. But in the years to come, his reputation was to be challenged as campaigning began for the office of censor. The censorship was a unique political office in the Roman Republic. Its holders were responsible for overseeing the census and property lists, alongside holding responsibility for public conduct and administering state contracts. This gave censors a significant amount of political power.

As elections for the censorship were infrequent, occurring every five years, achieving this office was highly competitive – and Cato failed at his first attempt in 189. However, five years later he was elected to become censor, and he immediately took it upon himself to impose conservative policies. This included raising taxes on luxury goods, alongside expelling a number of individuals from the Senate for various moral scandals and poor behaviour.

However, Cato also had ambitions to improve the lives of Romans in a more practical way, using his position as censor to build new roads and improving Rome’s sewage system. Cato could certainly be accused of being obstinate when it came to his ideology, but he could be forward-thinking when it came to administrative affairs.

At this point in his career, Cato the Elder was the most influential conservative in Roman society, championing traditionalist values and Roman ideals from the highest political positions in the republic. However, his staunch conservatism would continue to influence affairs within Rome. In 155 BC, more than thirty years after Cato’s election to the censorship, a delegation of Greek philosophers entered Rome and began teaching their beliefs. The philosophers Carneades and Diogenes had arrived as part of a diplomatic embassy from Athens, bringing their thoughts on stoicism and scepticism with them. To Cato, this was an affront to the traditional Roman values he had spent his career defending – discipline, hard work and the simple life. Even worse, the Roman youth flocked to these philosophers, keen to hear their teachings. As Plutarch reports:

The charm of Carneades especially, which had boundless power, and a fame not inferior to its power, won large and sympathetic audiences, and filled the city, like a rushing mighty wind, with the noise of his praises. Report spread far and wide that a Greek of amazing talent, who disarmed all opposition by the magic of his eloquence, had infused a tremendous passion into the youth of the city, in consequence of which they forsook their other pleasures and pursuits and were “possessed” about philosophy.

Cato “was distressed, fearing lest the young men, by giving this direction to their ambition, should come to love a reputation based on mere words more than one achieved by martial deeds” and when the philosophers were invited to speak before the Senate, he resolved to put an end to their diplomatic mission and have them removed from the city. Cato rose in the Senate and urged his colleagues “to make up our minds one way or another, and vote on what the embassy proposes, in order that these men may return to their schools and lecture to the sons of Greece”.

With Cato’s intervention, the diplomatic mission was sent back to Greece and essentially banished from the city, ending their rise to fame in Rome. Cato himself would spend the remainder of his career defending Roman traditions, alongside supporting an interventionist foreign policy against Rome’s great enemy, Carthage. His determination to end the Carthaginian threat once and for all led to him ending all his speeches in the Senate with “Carthage must be destroyed”.

Cato’s career is marked by his defence of tradition, simplicity, hard work and austerity. However, it also shows a broader theme within the Roman Republic: the influence of external ideas, and particularly Greek philosophy, on the Roman elite. This transformation of elite culture would accelerate even further as the Greek and Roman worlds became even more intertwined as Rome’s empire expanded further eastwards.

However, this clash between those who embraced these new ideological values and the conservatives who opposed them would continue until the end of the Roman Republic and into the imperial period. Cato may have achieved his goal of banishing the Greek delegation - and their philosophical musings - from Rome, but their thoughts would outlive their time in the city.

From the Optimates of the first century BC, who feared Julius Caesar’s ambitions to seize the state, to the moral reforms of Augustus Caesar a generation later, concerns over ancestral values and the moral fate of Rome would remain. The career trajectory of Cato and his fierce opposition to what he perceived as moral and philosophical threats to ‘Roman values’ showcases how elite values can change over time, alongside the conservative opposition that can emerge from such changes.